Victor saw the pope as a beacon of social justice, who would trigger the dictator’s demise.

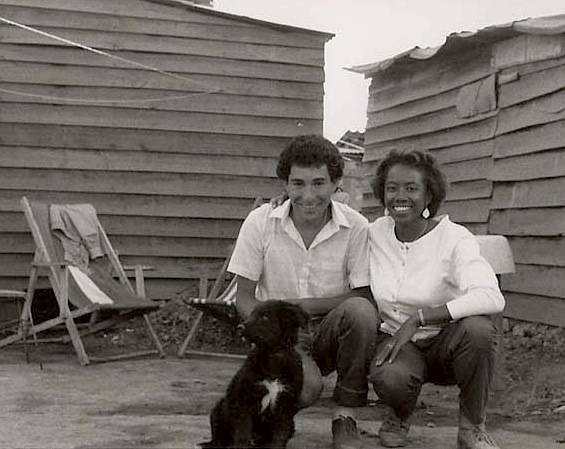

Editor’s note: In 1987, as protests against the Chilean dictatorship intensified, the author, then a graduate student in Chile, compared her views on poverty with those of her boyfriend Victor, a member of the opposition.

Victor was very excited about the pope’s visit. He held high hopes for the Catholic Church, which had been a vocal critic of the Pinochet regime and had reached out to poor communities like his, El Guanaco. The only institution to do so, the Church in Chile publicly linked Pinochet’s repressive regime with the stark contrasts of poor and wealthy families.

Before Pope John Paul II arrived, he made similar conclusions and announced them to journalists while on his chartered Vatican plane flying him from Montevideo to Santiago. In a moment of candor, he called the Pinochet regime a dictatorship and framed the pastoral mission of the Church as one that should fight for human rights.

“Some would want to separate us from this mission,” he said. “These people would want to tell us, ‘Stay in the sacristy, do nothing else.’ They say it is politics, but it is not politics.”

For Victor, other poor Chileans, and the opposition, the pope’s mere presence on Chilean soil could be nothing less than political. For conservatives, like my friends the Donosos, the pope’s visit was purely a sacred one. The pope had a fine line to walk, holding fast to a call for human rights, while also keeping his message spiritual, pastoral.

Official news sources did not carry the pope’s pre-landing comments, only the opposition paper, La Epoca, did, so a large majority was unaware of how strident the pope’s impromptu remarks had been. Yet expectations ran high, including Victor’s. He saw the pope as a beacon of social justice who would reprimand Pinochet and hence trigger the dictator’s demise. Everyone held his breath, waiting to see which side of the line the pope would walk on.

An Electrifying Arrival

The first day of the pope’s visit, our small group –Victor, his sister Elena, Rodrigo and me — waited with the rest of Santiago. Thousands of people lined the streets, expecting his Eminence, and suddenly he appeared.

The pope came through in his Popemobile, a vehicle with a clear, bulletproof casing that allowed him to stand and wave. I had my camera at the ready.

The crowd went mad as if welcoming a rock star.

I wasn’t Catholic, but the electricity of the moment buoyed me as if I too had a stake in Chile. I saw anticipation rise in Victor, the sort that lives in the belly of a child waiting for Christmas morning. He smiled and waved as el papa cruised by. This fleeting glance of the beacon of justice was Victor’s hope.

The next day the pope addressed Chile’s poor. The city practically shut down, major thoroughfares blocked to all vehicle traffic. We started the journey in the cool pre-dawn hours, walking deserted streets that slowly awoke. Our group grew as we made one stop after another to pick up friends. First we were the four from the previous day. Then we were six, then 10. We walked south for a long time. My legs began to tire, but I wasn’t about to complain.

The closer we got to the site, the thicker the crowds became. We arrived at La Bandera, another poor campamento on the outskirts of the city. The sun rose higher into the sky and we began to feel the warmth of the day. The stage and podium were set for the pope, and the Andes mountain range - La Cordillera - stood resplendent and regal in the background. I could barely breathe.

Finally, the pope took the stage. Applause roared as red, white, and blue Chilean flags waved back and forth. Banners and yellow and white Vatican flags fluttered in the breeze as the people declared their love of the pope. The crowd went on for miles in every direction.

Before the pope spoke, a few of Chile’s poor testified to their circumstances: No health care, no work, poor schools for their children, political repression. As each speaker finished, the pope stood to embrace and kiss him or her.

Then he began his address. Turning to the speakers on the stage, he told them how their comments deeply moved him. He turned to the expansive crowd, raised his arms to the sky as if asking God for alms and began to speak.

He urged Chilean society to have more compassion and respect for the poor and their plight. He praised the Church’s work to organize and help sustain communities. He reminded the poor that material desires were not the answer to spiritual want. He deftly alluded to political repression, but never once directly called Chile a dictatorship nor did he call for Pinochet’s removal.

Yet, this was what Victor and his friends had been waiting for. Not once while on Chilean soil did the pope strike the bold notes intoned on the Vatican flight.

And Disappointment

For Victor, the rally at La Bandera fell short. He wanted, needed a direct denouncement of Pinochet — he expected political action. What he and his friends got instead was a speech full of spiritual encouragement.

I thought the pope’s words were moving, so much so that I considered a conversion from Presbyterianism to Catholicism. I couldn’t understand why Victor and his friends would expect the highest priest of the Catholic Church to take political action. He’s the pope, not the U.S. Secretary of State. While I had vague notions of the Chilean Catholic Church’s support of the poor, at that moment I did not know that the Catholic Church in Chile had taken an active opposition to the regime, calling for a return to democracy and publicly denouncing political repression and the regime’s neglect of the poor.

Because the Church had struck a political posture, it made sense for Victor and his crew to expect the same from the pope. But Juan Pablo II wanted to keep the Church’s message spiritual, and he tugged on the cassocks of Chile’s bishops and priests, who had veered too far into the political wetlands.

Not knowing what I didn’t know, I hinted at my good feelings about the speech, but knew I couldn’t say much. I wasn’t Catholic. I wasn’t Chilean. And I wasn’t poor, certainly not as poor as Victor and his friends.

Poverty as a Social Problem

“Poverty is a political problem,” Victor told me one day.

We were at St. Lucia [Park] one evening. I had finished with school for the day and he with work. The pope was long gone and the tingling thrill of his visit had dissipated. Victor and I often met in the park. It was the most central place for us to meet, more so than El Guanaco or La Reina, where I lived with the Donoso family. We walked holding hands then sat to continue talking.

I pulled knitting from my bag, a hobby I had resurrected while in Chile, to work on a sweater for Victor to keep him warm in his damp, cold lean-to. It was common and more proper for young lovers to meet in the park rather than someone’s home. In the park they could kiss without the watchful eyes of parents or teasing tongues of siblings. If they were unmarried, couples’ time in the park was precious. Pairs of lovers dotted various benches. Love was contagious. Even married couples with their families cooed at each other as their kids played.

Victor and I sat near a column that once supported an unknown structure.

?I think poverty is more of a social problem,” I responded. In my mind, people decided that one or two groups were less worthy and so stacked the deck against them — consciously or not– and kept them from opportunities that would allow them to rise out of poverty.

My conclusions were not based on tested economic or sociological theories, but I did feel like I had a handle on the reality of marginalization. As an African American, I saw both the visible and hidden hands of injustice wielding power and thwarting opportunities in the U.S. Sometimes that power was political, but often it was structurally embedded in society.

Growing up in the Chicago area, discrimination was not new to me. While my personal experiences with prejudice were limited, I knew intimately the stories of family members and family friends. Even when we lived in the suburbs, I saw class and racial inequality play out daily.

At my suburban high school just south of Chicago, most black kids were tracked in the lower level classes. Those few blacks who were in the upper-level classes tended to come from the right side of the tracks, in this case that track was a four-lane road called Western Avenue, cutting the middle-class suburb Park Forest off from the impoverished Chicago Heights neighborhood called Beacon Hill. I sat in my honors English and high-level math with one other African American, a brother who happened to come from Beacon Hill — that one exception to the rule.

I always wondered if I really belonged in those courses. I did well enough, but I knew I wasn’t any smarter than my black peers. But tracking made one believe they were better than those placed below them, better than the folks from Beacon Hill, that suburban ghetto across the border. Such segregation afforded the illusion of superiority and hid more structural reasons — poor education prior to high school, poorly-distributed resources — behind the poor performance of my black classmates.

When our family took outings to visit friends on the south side of the city, I was always struck by the dreariness and desolation of the streets. I would often feel like our family was somehow lucky to have escaped such fate. I knew these people well and knew that they worked as hard as any of us. But I also knew they were limited by their circumstances. Poor schools. Low wages. Illness. These were social problems, whose solution could be political, but rarely ever was.

In fact, politics seemed to make these problems worse, because poor and poor blacks particularly were used as wedge issues, and they carried little political leverage. Our family was never really political, and we held little faith that politics could do anything for us. My own political awakening happened when I left home to go to college. There, I witnessed the Carter years of conservation and compassion give way to Reagan-sparked debates of welfare queens and racial preferences. There my political compass made a hard left.

On a political level and many others I understood Victor and his disconsolation, his yearning for a solution to his personal circumstances and that of his family’s.

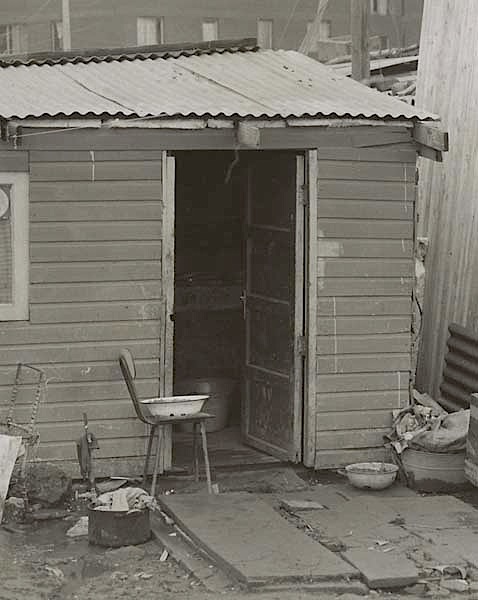

But for me, this fight was ideological, academic, less immediate. No matter how much I empathized and tried to place myself in his shoes, I did not have to go home to a dark shack with no windows or running water. I was a visitor, a mere guest to poverty, never having to eat, drink and sleep with the facts of being poor.

Venise Wagner is an associate professor of journalism at San Francisco State University. This is an excerpt from her new memoir, “Love in the Time of Pinochet.”

What's your view?

You must be logged in to post a comment.