At the storied New Yorker Hotel, the author discovers a trove of artistic menus meant to evoke the glamour of the ’30s and ’40s

During World War II, my late father was a sailor stationed on Long Island near New York City. Every weekend, he’d travel to the city and book a room at the New Yorker Hotel.

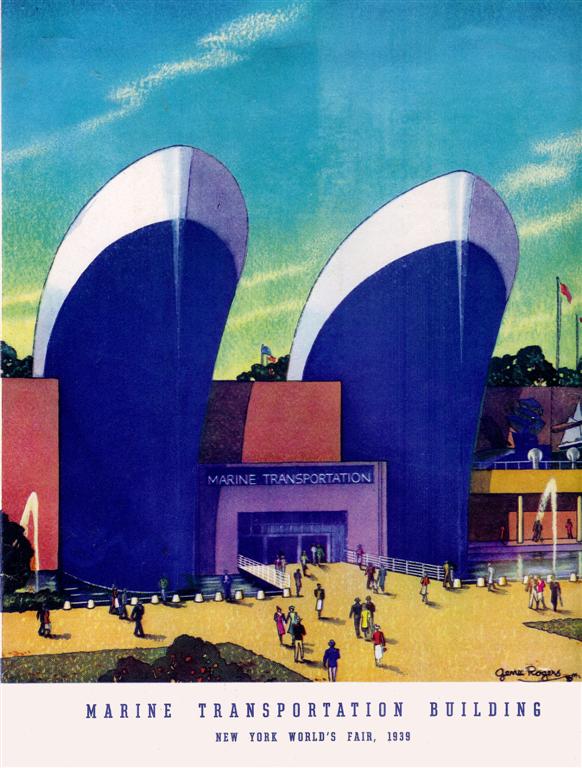

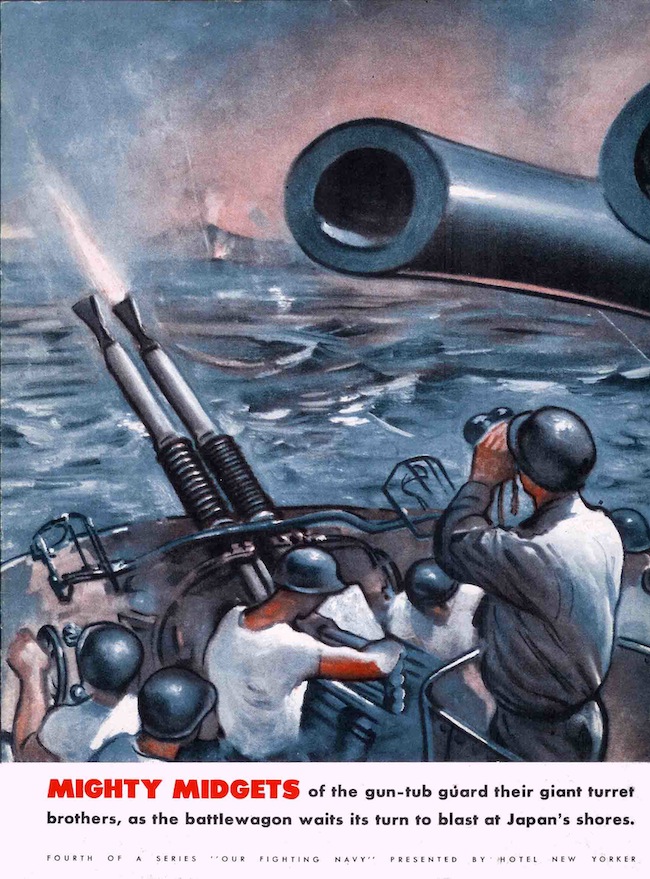

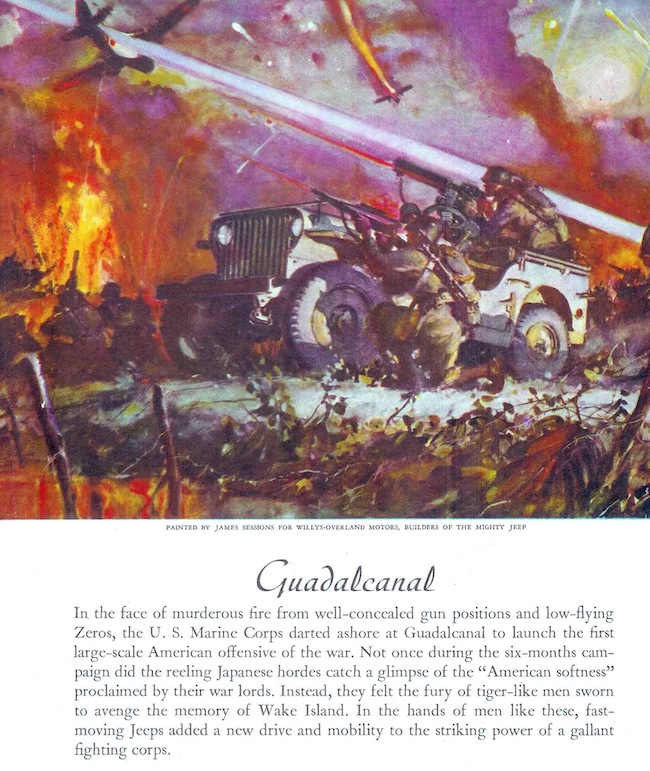

Once seated in one of the New Yorker’s four restaurants, he would have been handed a menu. Many had dazzling artist-created covers. These stunning works of dining art were unusual in their vivid use of color and artful designs. Whether depicting brightly-hued pavilions at the 1939 World’s Fair or stirring battle scenes, the menus evoked the glamour and excitement of New York in the ’30s and ’40s.

Almost certainly the brainchild of the New Yorker’s first president, Ralph Hitz, the beautiful menus were not an accident, Hitz’s granddaughter, Suzanne Creps, told me. “He was extraordinarily into detail.”

They made a “visual statement,” that the New Yorker was “beating with the pulse of the city,” said William Grimes, author of Appetite City, a history of New York’s restaurants.

Diners were treated to depictions of the three baseball teams New York had back then, and of the World’s Fair pavilions, dedicated to aviation, gas and other themes. After World War II broke out, menus depicting wartime themes appeared, like a series that paid homage to the rugged battlefield vehicle, the Jeep.

I stumbled upon the menus after meeting Joe Kinney, the New Yorker’s chief engineer and informal archivist. His basement office is stuffed with 1,500 hotel artifacts, some dating from the hotel’s opening in the 1930s.

Kinney told me that the Terrace Room nightclub was “by far the most famous” eatery at the hotel. Celebrities like Jean Harlow and Babe Ruth used to dine there, and to dance to the strains of the Benny Goodman or Tommy Dorsey bands. Guests also watched elaborate ice shows on a retractable 9-ton rink.

Meanwhile, in the enormous kitchen, over 100 chefs would prepare as many as 10,000 meals a year, sourcing local ingredients like cherry stone clams and Cornell University College of Agriculture-bred eggs.

In fact, the New Yorker menus illustrate a common hotel restaurant formula of the day: American standards with the barest whiff of French sophistication. A hotel brochure touts Alsatian goose liver, meant to render the cuisine, heavy on items like ham hash with poached eggs, “a teeny French,” as New York City food author Arthur Schwartz put it.

Today, the New Yorker is owned by the Unification Church. The kitchen’s handful of cooks caters strictly to business events.

“It’s a different world,” sighed Executive Chef Paul Valin.

Journalist Laura B. Weiss is the author of Ice Cream: A Global History. She blogs at Food and Things.

What's your view?

You must be logged in to post a comment.